I question our practice of painting biblical heroes more heroically than the Bible does. Hiding the faults of our heroes robs us of grace. That’s why the Bible doesn’t hide them.

I once suggested we tell true stories of our heroes, stories that show God’s pursuit of them despite their failings. I pointed out:

- Abraham was an idol worshiper and God loved him and pursued him;

- Joseph was a narcissistic boy and God loved him and pursued him;

- David was a murdering adulterer and God loved him and pursued him;

- Esther had sex outside of marriage with a non-believer and God loved her and pursued her.

I was surprised by the many readers who were upset at my negative description of “good” Abraham, Joseph, and David. I wondered, “Have they even read those stories?”

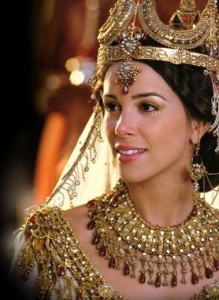

But I was astonished at the hail-storm of hundreds of angry emails that hated my history of Esther. Esther is beloved. Many think she was forced into sexual slavery.

I think she was a complicit adulterer.

Why won’t we admit any shortcomings in our heroes?

Let’s put aside (for a moment) Esther’s willing compliance or innocence. Why do we begin reading the Bible with a built-in bias for these heroes to have an innate goodness?

Nowadays we want think Esther was pure as the driven snow, but readers for over two thousand years thought otherwise. When early readers read Esther, they saw moral ambiguity at best. And like us today, they did not like it:

- The first translations into Greek added words to “improve” Esther’s character, saying she never violated kosher law and she abhorred the bed of the gentile.*

- For the first seven hundred years of the Christian church no one—not one person—wrote a commentary on Esther.

- Luther wrote, “I am such a great enemy of the book of Esther that I wish it hadn’t come to us, for it has too many heathen unnaturalities” (slightly edited).

We are biased. We want Esther (and other heroes) to be naturally good because we misunderstand the evil within ourselves, and we fail to grasp grace. Instead we grasp for high self-esteem, and believe God primarily works with inherently good people. Like us.

How would a person who feels broken receive Esther?

A woman called me shortly after my villainous questioning of Esther’s purity. She had been raped as a sixteen year-old by an uncle. She spent the next ten years using her body to gain men’s affection, even occasionally for money. She said,

“When my uncle raped me, it was mostly the force of his personality, but there was a tiny bit of me that was complicit. I didn’t resist, partly because I wanted the attention of any man who at least wanted something I had. In subsequent encounters [with the uncle] I even took the initiative.

“Now [over twenty years later] I understand the brokenness of that little girl who was abandoned by her father; I understand the innocent longing for affirmation; I feel for that little me that was confused and without tools to cope.

“But I still felt guilty for the little part of me that participated. I thought, ‘God could never use me.’ Then I read Esther and understood that God can make even the smallest into something great. The story of Esther brings me hope.”

Her uncle was monstrous. He is guilty of abominable exploitation of a young woman’s personal confusion. But I sympathize with her confusion, and I love the comfort she receives from Esther.

It is her brokenness that allows her to see (and draw hope from) Esther’s brokenness. The person who feels an innate goodness refuses to see God’s heart-changing grace.

Does God use us because we are born good? Or does God take the most broken—even the most brutalized—and turn us into “possible gods and goddesses that if others saw now, they would be strongly tempted to worship”? (C. S. Lewis, slightly edited)

Where will God receive the most glory; in the natural strength of our intrinsic goodness, or through the majesty of God’s supernatural, transforming grace?

So what about Esther?

Esther lived in an age of brutality beyond my imagining. Hundreds of girls were taken for the king’s harem. Perhaps some saw it as an opportunity, but many must have hated it.

The age was also brutal to men. Every year five hundred boys were taken captive and castrated to serve as eunuchs in the Persian court (Herodotus 3.92).

Scripture never mentions Esther’s inner life. It only describes her behavior. It neither says “She wanted to be queen,” nor says “She loathed the idea.” It only describes her behavior. And what is that behavior?

- Scripture commends Daniel for identifying as a Jew and not defiling himself with unclean food. Esther assimilates and eats all the food provided.

- Shadrach, Meshach, and Abednego resist their king’s command under threat of a fiery death. Esther pleases her king more than all the other virgins of the harem.

- Ezra condemns any Jew who marries a Gentile. Esther loses her virginity in the bed of an uncircumcised Gentile she marries only later, and is crowned queen.

Some say that Esther had no choice; others say she should have resisted to the point of death. Some even say suicide was preferable to allowing that defilement.

How would I have done?

Far, far worse. As a kid I used to wish I had been one of the disciples so I could have been the lone friend who didn’t abandon Jesus. As an adult, I know myself better.

I admire the bravery of the disciples—not of course their “bravery” during the crucifixion—but their bravery in detailing their faults in the Gospels. The Gospels overflow with their ambition, stupidity, and cowardice.

That took guts. Why do you think they wrote the gospels that way?

And something changed in Esther

Esther’s predecessor, Queen Vashti, was banished for defying the king. Esther won the king’s favor by not defying him. Yet the book climaxes when she finally does defy him.

In making her decision she exclaims, “If I perish, I perish.” It reminds me of the men before the fiery furnace who say, “Our God can save us, but even if he doesn’t….”

Why do we want our heroes to have been so good?

Karen Jobes wrote a terrific Commentary on Esther. She says,

“Other than Jesus, even the godliest people of the Bible were flawed, often confused, and sometime outright disobedient. We are no different.”

Let’s not falsely disparage biblical characters, but let’s not ignore their failures either. Because we are no different: flawed, confused, outright disobedient, and proud.

Why do we want our heroes to be better than they really are? Because we think we are better than we really are. We would see more of God’s transforming grace if we spent more time acknowledging our own failures, just like the Bible does of its heroes.

After all, God can raise up inanimate stones to be his righteous ones.

Isn’t it more hopeful (and truer to the gospel) that God’s miraculous, transforming power is wonderfully displayed for all the world when he takes the broken stones we are, dips us into the furnace of his love, and out we come as nuggets of pure gold?

God can make the littlest great; but he can’t use the greatest until we become little.

Sam

* Greek translations of Esther add six long “chapters” which scholars identify by letters A through F (to distinguish them from the Hebrew chapters that we number). Section C:26 adds, “[God,] you know I abhor the bed of the uncircumcised,” and C:28 adds, “[I] have not eaten with them at their table.” See this translation of the Greek additions.

© 2013 Beliefs of the Heart