I once belonged to a prayer group that prized ecumenical unity. We came from a wide variety of Christian traditions. We sang, “We are one in the Spirit, we are one in the Lord.” Then we split down the middle due to ruptured relationships among our leaders.

We formerly prided ourselves on our exceptional unity; then our leaders attacked each other. We were embarrassed and a bit humiliated. Our highly prized treasure—good relationships in the midst of very strong differences—had slipped from our grasp.

A fellow member heard of a Christian leader in a neighboring city who had committed adultery and raided the group’s bank accounts. Sitting next to me in a prayer meeting, my friend shared the story and then whispered, “At least we’re not that bad.”

A fellow member heard of a Christian leader in a neighboring city who had committed adultery and raided the group’s bank accounts. Sitting next to me in a prayer meeting, my friend shared the story and then whispered, “At least we’re not that bad.”

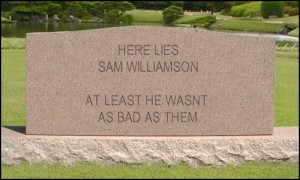

“Great!” I thought, “that’s just what I want chiseled on my tombstone:”

Here Lies Sam Williamson

At least he wasn’t as bad as them

What’s the real problem?

Criticizing legalism is popular today. It should be. But our critiques miss the point. We think of legalists as fussy, prudish, authoritarian, rule makers. They turn the tiniest commandment into a drudgery-filled dictionary of rules for joyless living.

Legalists remind us of the severe, unsmiling Pharisees. But that’s unfair to the Pharisees. Pharisees began as the good guys. They cared for the common folk and protected them from false religion. They taught the Bible and opposed the snobbish, priestly class.

Legalists don’t begin as joyless, fastidious, rigid dogmatists. That’s just the way they end up. Sure, legalists are rule-makers; but they create rules to make themselves feel good.

The result of their rules is the real problem. Their rules create a cultural sense of superiority. Somehow—because of their rules, or understanding, or man-created culture—somehow something about them is better.

If we limit ourselves to two simple rules, “Love God and love your neighbor,” we’ll feel more spiritual than those fundamentalist, killjoys. If we only make one rule, “Never make rules,” we’ll somehow feel better than those rule-manufacturing, stuffed shirts.

At least we aren’t as bad as them.

Besides, manmade rules aren’t strict enough

A religious lawyer tells Jesus that the Law can be summed up by two commands:Love God and love your neighbor. Jesus replies, Good job, now go and do it. The lawyer then asks, “Who is my neighbor?”, but he asks, “in order to justify himself” (Luke 10:29).

The lawyer doesn’t ask how he can do the impossible (that is, love unlovable people). No, his question asks, “What is the absolute minimum behavior I can get away with?”

He wants rules he can handle. He says: Give me rules that I can observe; tell me just to love neighbors within fifty yards, or to love only like-minded believers in my circles.”

The problem with rules made by legalists is that they aren’t strict enough. Rules made by God drive us to him because we can’t possibly accomplish them on our own; rules made by legalists drive us to performance, self-identity, and superiority.

It’s counter-intuitive, but rules made by legalists are never created to make life difficult. They are made so we can live up to these standards and so feel good about ourselves.

That’s why Jesus answers him with the Good Samaritan parable. We can’t be that loving. We need God to change our hearts. And that’s the point. God’s rules drive us to him.

What’s the hidden problem?

Let’s admit the secret problem with legalism’s superiority: We are all guilty.

- Charismatics scorn (in their spirits) the Frozen Chosen;

- Academic theologians sneer (in their intellects) at devotional writings;

- John Eldridge fans pity (in their hearts) believers who won’t admit their wounds;

- Lay people scoff (in their ignorance) at those egg-head, doctrinaire hairsplitters;

- And anti-bigots are bigoted (in their tolerance) against bigots.

Everyone feels superior. Reading this article, some will think: I’m not perfect, but at least I’m not as bad as those self-deceivers who won’t admit their own imperfection!Our deep-seated need for applause compels us to affirm ourselves at the expense of others.

Everyone’s guilty. Everyone’s a legalist. Except you and me (and I’m not so sure about you.)

Who lives beyond fifty yards of us?

My ecumenical prayer group had Protestants, Orthodox, and Roman Catholics. We felt a [right] conviction to be known as Christians because of our love (John 13:35). We wanted to show it is possible to love other believers who greatly differ from us.

But our “rule” of ecumenical-loving was a standard we could obey. We were a group of like-minded believers who shared an ecumenical value. We could achieve it. We came from the 60’s and 70’s generation that sang, “If I had a hammer, I’d hammer out love … all over this land.” Denominational hatred was naturally anathema to us.

Our parents’ value of theological primacy was simply not as important to us as it had been for them. Our ecumenical miracle wasn’t as miraculous as we prided ourselves. It was a neighbor within fifty yards.

Then a difference of opinion arose that was important to us; we argued and we divided.

We once felt superior to our parents who failed to fight for ecumenical unity. When we faced our own battle for unity, we too failed. We ended up realizing we were “just as bad as them.”

And that is a very good place to start.

Sam

P.S. I still highly value love across all Christian traditions. But if we succeed, let’s not feel superior. For some, ecumenism isn’t that difficult (it was our parents’ battle not ours); for others, ecumenism is still hugely difficult today.

Let’s prize unity. Let’s express it beyond ecumenism. Let’s also love when we disagree over mission budgets, worship styles, and various Christian movements. The world will know we are Christians if we still love even—maybe especially—when we disagree.

Avoiding The Pain of Regret

Avoiding The Pain of Regret

Leave a Reply