As a young boy, my weekends were filled with imaginary World War II battles. Nearby parks fielded the Battle of the Bulge, and the skeleton of a local building project (fatefully a new funeral home) formed our bombed-out buildings.

Dirtballs became our hand grenades, ditches our foxholes, and blankets our pup tents. We sacrificed our bodies (and the knees of our jeans) to save the world from Hitler.

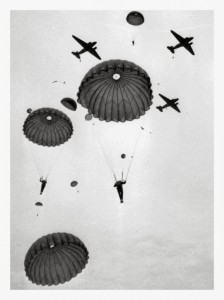

One Friday evening I watched the movie, D-Day. I was captured by the airborne parachute jumps, the bravery and heroism, and the infiltration behind enemy lines.

The next day I made my first (and last) parachute jump. I confiscated a sheet from my mom’s closet and requisitioned rope from my dad’s tool room. I tied one end of the ropes to the corners of the sheet and the other ends around my chest.

I slithered through an upstairs window and crept onto the roof. With my parachute and lines carefully laid out behind me, I perched at the edge of our second story, and I hurled myself into the air behind enemy lines. I waited for the tug of the opening chute.

Lying on my back, I looked up. The chute still lay on the roof, and the carefully cut lines hung limply over the gutter. I had forgotten to measure the height of the roof.

My lines were ten feet too long.

The modern day tension of heroic virtues

Several hundred years ago, our ancestors ranked courage among the highest valued virtues. They faced daily threats from diseases unmitigated by antibiotics, frequent farming accidents (unrelieved by 911 calls), high infant mortality rates, and marauding bands of outlaws. They needed daily courage.

But technology and modern medicine have largely eliminated our need for everyday courage. How many of us (in the Western world) regularly face real terror?

So certain intelligentsia-circles pooh-pooh old-fashioned virtues like courage.* In response, C. S. Lewis points out the irony of our modern culture’s virtue vacuum:

In a sort of ghastly simplicity we remove the organ and demand the function. We make men without chests and expect of them virtue…. We laugh at honour and are shocked to find traitors in our midst. We castrate and bid the geldings be fruitful (The Abolition of Man).

This contempt of courage is evident in the silly stars of modern sitcoms. They are often good for nothing (or good for only a laugh), cowardly nincompoops, or effeminate moral slugs. (Even the movie version of The Lord of the Rings emasculated the original courage of Théoden, Faramir, and Treebeard.)

I’m a tad ashamed to admit to a tiny attraction (along with my repulsion) to sitcoms like Seinfeld and The Big Bang Theory. I wonder if my parent’s World War II generation would have tolerated such shows

But we have a problem

Our culture, with its modern medicine and technology, shields us from the ancient horrors faced by our forebears. Yet—despite ambulances and antibiotics—our mortality rate remains unchanged.

One hundred percent of us die. And death is an enemy we are unprepared to face.

Much of our technological drive is an attempt to hide from death. Modern thinkers agree that we have a deep, hidden fear of death.** If death is “it,” everything we do is insignificant. Nothing makes a difference. So we repress the horror of death. However, even though we repress it, deep down inside we still fear it.

If death is annihilation, then nothing we do—in the long run— will ever matter. But what if death isn’t the end? That too is a problem. Epicurus, wrote,

If we could be sure that death was annihilation, then there would be no fear of it. For as long as we live death is not there, and when death does come, we no longer exist. But we cannot be totally sure death is annihilation. What people fear most is not that maybe death is annihilation but that maybe death is not.

I’d like to live an epic life. I bet you do too. But if death is the final end, our heroism will be forgotten when the sun dies. And if death isn’t the end, our self-centered cowardice will live forever.

What are we to do?

Death is not just another archenemy with a chink in his armor. Death is the final enemy that we cannot beat.

Death is our Goliath. Sure, the army of King Saul’s Israel were chickens, but they were reasonable chickens. They knew they’d lose against Goliath. They didn’t have a chance. They could be sixty-seconds heroes, and then die. And soon be forgotten.

When we read the story of David and Goliath, where do we see ourselves? Are we the hero David? I hate to break the news, but we are the cowardly army; we are the selfish Seinfeld and cowardly Sheldon. I don’t like it, I try to hide it, but I’m not that epic hero.

Because Death is the enemy I have no chance of beating.

But there was one

When little boy David faced Goliath, he faced the monster alone. He didn’t call to Saul’s soldiers with “Hey everyone, group huddle.” He didn’t elicit courage from them with the self-hypnosis of, “Come on, let’s imagine ourselves beating him up.”

He face Goliath alone. With unimaginable courage.

Jesus was our David. Only he didn’t face a hulking human, he faced the giant we had no weapons to fight, unconquerable sin and unbeatable death. And he didn’t fight with the hope of winning, he fought knowing that only our hope was his death.

Unlike any god of the ancient world; unlike the sappy stars of sitcoms; unlike modern superheroes relying on their superhero strength; our God has courage.

Our first (and last) parachute jump

When I jumped—like the idiot boy I was—from our second story roof, I don’t know how I survived unhurt, but survive I did. No broken bones, no twisted ankles, and no pulled muscles. Not even a tear in my jeans (my biggest fear was fear of my mom).

But there is a jump everyone inevitably makes; it’s the leap of faith we all make with our hopes. Will we make that leap with the world’s jury-rigged chute of sheets and ropes of self-created heroism, self-numbing comfort, and denial of death?

Or will we leap with only parachute that will truly save us? Once sin and death has been destroyed, we can finally be heroic, our worst enemy is dead; and our parachute lines are just right.

We can finally face anything.

Sam

+++++++++++++++

© 2013 Beliefs of the Heart

Leave a Reply